Why Vision Screenings Aren’t the Same as Eye Exams

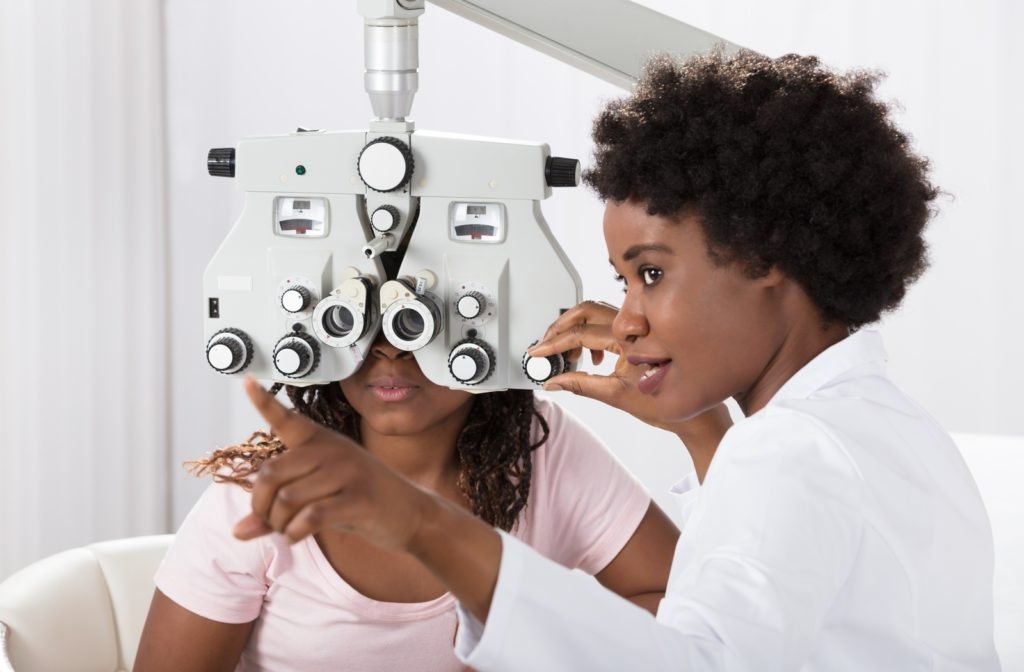

Vision screenings are common. Many of us remember doing them in school; standing in a hallway, covering one eye, reading letters off a chart. These screenings play a role in public health, but they’re often misunderstood. A vision screening is not the same thing as a comprehensive eye exam, and relying on screenings alone leaves many vision problems undetected.

What vision screenings actually do

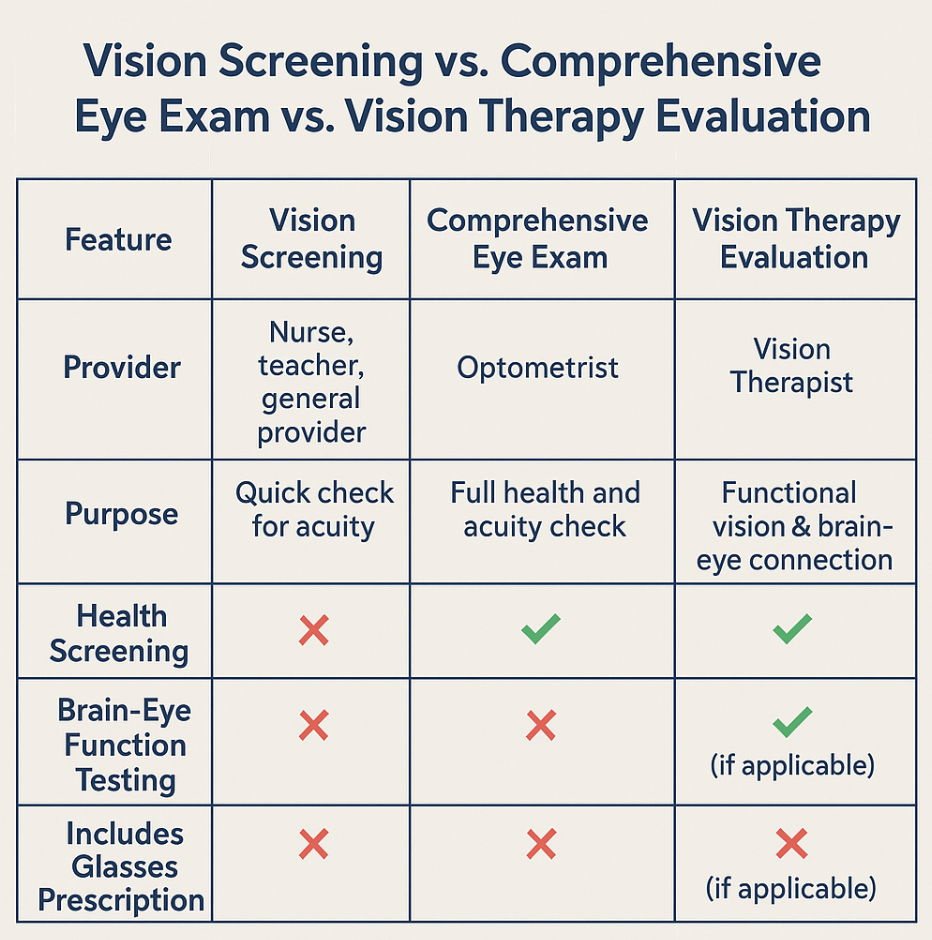

Vision screenings are designed to flag potential problems, not diagnose them. Most school or pediatric screenings focus almost entirely on distance visual acuity—how clearly a child can see letters on a chart from far away. They’re typically quick, use minimal equipment, and are often conducted by non–eye-care professionals.

Because of this limited scope, screenings do not assess:

eye health

focusing ability

eye coordination or teaming

subtle refractive errors

binocular vision problems

In other words, a child can “pass” a screening and still have a meaningful vision issue. However vision screenings are still an essential step of eye care. Therefore, it’s also worth noting that not everyone even gets a vision screening, especially outside of school settings. Screening requirements vary by region. For example, as of 2020 only 40 U.S. states mandated some form of vision screening for school-age children (Moyer, 2025). Many preschoolers don’t receive routine screenings at all. A federal survey found that by 2016–2017, only about 64% of U.S. children aged 3–5 years had ever had their vision tested by a professional (Black, Boersma, & Jen, 2019). That means over one-third of preschoolers had never been checked that early in life.

What a comprehensive eye exam includes

A comprehensive eye exam, performed by an optometrist or ophthalmologist, evaluates how the eyes see, work together, and remain healthy. In addition to acuity, exams assess refractive error, eye movement, focusing, binocular vision, peripheral vision, and internal eye health—often with pupil dilation.

This matters because many common pediatric vision problems don’t reduce distance clarity. For example, children with focusing or eye-teaming difficulties may see the chart clearly but struggle with reading or near work (Solan, 1988).

In short, a comprehensive exam is head-to-toe for your eyes, whereas a screening is more like a quick temperature check. An exam results in a diagnosis (if there’s any issue) and a treatment plan – e.g. prescription glasses, vision therapy exercises, medication, or referral for surgery, depending on what’s found. Only licensed eye care professionals can conduct these exams because they involve medical judgments and sometimes advanced tests.

What screenings often miss

Research consistently shows that screenings overlook many issues that affect learning and development. Conditions such as amblyopia, convergence insufficiency, accommodative disorders, and early eye disease frequently go undetected without comprehensive exams (AAP et al., 2016).

The AOA estimates that about 1 in 4 school-aged children has a vision problem significant enough to interfere with learning (AAP et al., 2016). Yet many of these children pass basic screenings.

There’s also a follow-up gap. Studies show that more than half of children who fail school vision screenings never receive a comprehensive eye exam afterward (Zhang et al., 2019). In those cases, the screening identifies a risk—but no care follows.

Why this difference matters

Vision plays a central role in learning, coordination, and comfort. Undetected problems can contribute to reading difficulties, attention concerns, and academic frustration. In some cases, vision issues are mistaken for behavioral or learning disorders when the underlying problem is visual (Solan, 1988).

Screenings are useful for identifying obvious concerns in large populations, but they are only a first step. A comprehensive exam is what actually determines whether a child’s visual system is developing normally and functioning well.

For children especially, regular comprehensive eye exams are the most reliable way to ensure vision problems are identified early, when intervention is most effective.