When children’s vision started to become specialized (1940s–1960s)

By the time the 1940s rolled around, children’s vision care was no longer just a side effect of school screening. It was becoming clear that kids didn’t just need earlier exams but rather, they needed different exams. This is the period where specialization really starts to take shape, even if it still didn’t carry the name ‘pediatric optometry.’

What’s interesting about this era is that two things happened at once:

medical doctors began formally separating pediatric eye care from adult ophthalmology, and optometrists began expanding how they thought about vision in children.

Pediatric ophthalmology becomes a thing

On the medical side, the 1940s are usually marked as the beginning of pediatric ophthalmology as a subspecialty. In 1943, ophthalmologist Frank D. Costenbader limited his practice exclusively to children, something that was unusual at the time (Costenbader, 1950). He’s often cited as the first physician to do so.

His work—and later that of Marshall M. Parks, who helped formalize training and professional organizations—made one thing clear: children’s eye care required its own knowledge base and approach (Parks, 1975).

For optometry, this mattered even if it was happening in a different lane. It reinforced the idea that children’s eyes weren’t just smaller adult eyes, and that development mattered.

Optometry starts thinking beyond acuity

Around the same time, optometrists were re-examining what “vision” actually meant, especially for children. Instead of focusing only on clarity (20/20 vs. blurry), some practitioners began paying closer attention to how kids used their eyes—how they focused, how their eyes worked together, and how vision supported movement and learning.

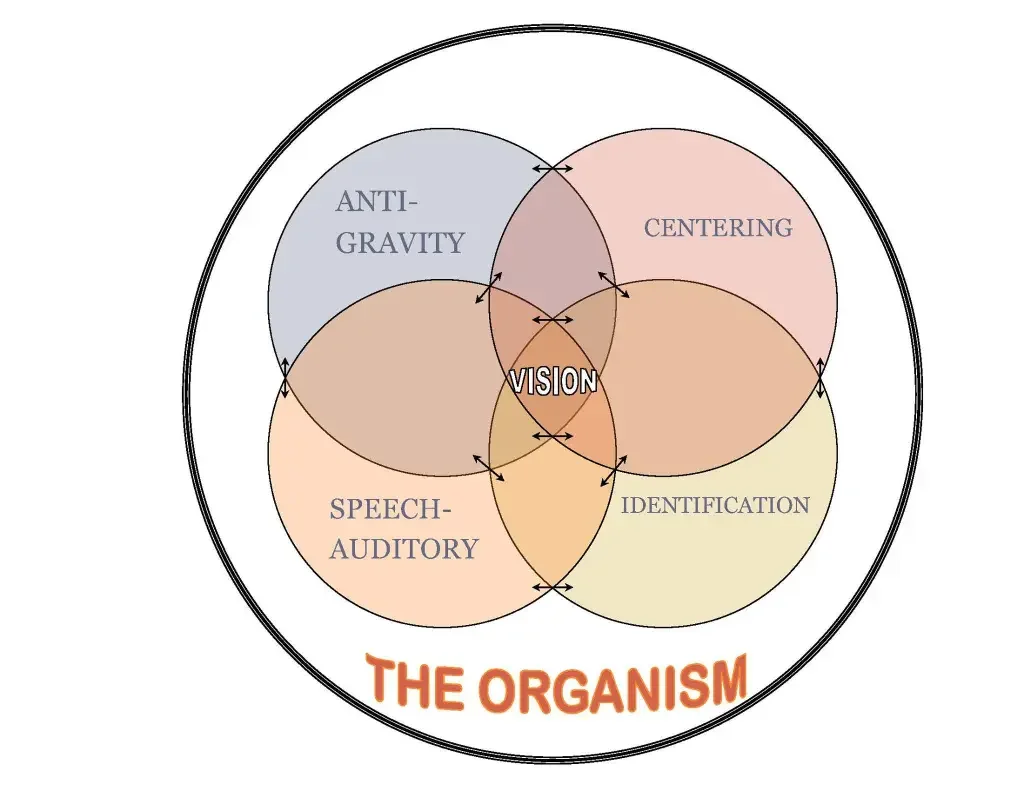

One of the most influential figures during this period was A.M. Skeffington, whose work helped shape what became known as behavioral or developmental optometry. Skeffington argued that vision was an active process involving the eyes, brain, and body—not just a static measurement (Skeffington, 1957).

This way of thinking fit naturally with pediatric care. Children were developing constantly, and vision development was part of that process.

Vision therapy and binocular vision

As this perspective gained traction, optometrists began using structured visual activities—what we now call vision therapy—to address conditions like amblyopia, strabismus, and binocular vision disorders. These approaches weren’t invented overnight, but the mid-20th century is when they became more organized and more widely discussed within optometry (Press, 1997).

It’s important to note that this work didn’t exist in isolation. Orthoptists (especially in hospital settings) were also treating binocular vision problems, and ophthalmologists were managing surgical cases. But optometrists increasingly found themselves managing functional vision problems, especially in children who struggled with reading or near tasks.

Infant vision research changes the conversation

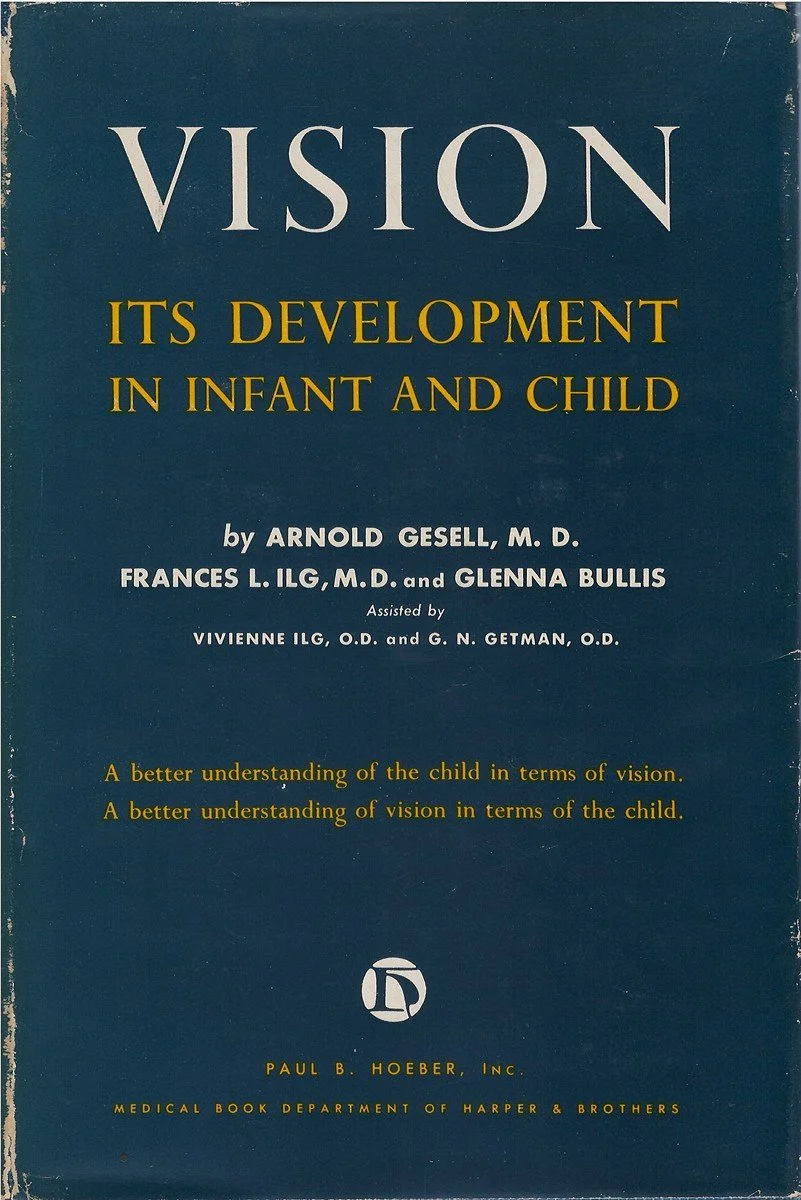

Another major development during this period was the growing interest in infant vision. In the 1940s, psychologist Arnold Gesell collaborated with optometrists G.N. Getman and Vivian Ilg at Yale to study visual development in infants and young children (Gesell et al., 1944).

Their work documented how visual skills—like tracking, focusing, and coordination—develop over time. This research helped support the idea that vision problems could exist well before a child entered school, and that waiting until academic struggles appeared might be too late.

This research helped to quietly influenced optometry education and clinical thinking. If vision develops early, then eye care should start early too.

Education and professional culture

By the 1950s and 1960s, optometry schools were teaching more about pediatric vision, binocular vision, and developmental concepts, even if formal pediatric tracks didn’t exist yet. Journals within optometry published increasing numbers of papers related to children’s vision, learning, and visual perception (Solan, 1966).

The Optometric Extension Program (OEP), founded earlier in 1928, became an important space for practitioners interested in these ideas. It provided continuing education and a professional community focused on vision development across the lifespan, with children at the center of much of that work (Sutton, 2005).

The idea that preventative vision care (catching problems early, doing vision therapy, etc.) could help children succeed in school was really taking root.

School screening continues—and referrals grow

Meanwhile, school vision screening programs expanded throughout the U.S. During this period, many states adopted routine school screening, often with endorsement from medical organizations (Appelboom, 1985). While screenings still had limitations, they increased referrals to eye care providers.

For optometrists, this reinforced their role as primary providers of children’s vision care. Kids identified at school were increasingly seen in optometry clinics for full exams, glasses, and follow-up.

Where pediatric optometry stood by the 1960s

By the end of the 1960s, pediatric optometry still wasn’t formally labeled as a specialty—but it was clearly forming:

pediatric ophthalmology existed as a defined medical subspecialty

optometrists were actively managing children’s vision development

vision therapy and binocular vision care were becoming structured

infant and early childhood vision research was influencing practice

optometry education was slowly adapting

Part 3 is where pediatric optometry becomes recognizable as a specialty—through residencies, certifications, textbooks, and formal recognition in the late 20th century!