Recognition, training, and the point where it became a specialty (1970s–1990s)

By the 1970s, pediatric optometry had moved past its informal phase. Optometrists had been caring for children for decades, school screenings were routine, and developmental ideas were well established. What changed during this period wasn’t interest but rather structure!

This is the era where pediatric optometry starts to look like a specialty rather than just an area of focus within general practice.

Postgraduate training enters the picture

One of the biggest shifts came with the expansion of optometric residency programs. Residencies existed earlier, but in the 1970s and 1980s they began to diversify. Programs focused on pediatric and binocular vision started appearing at academic institutions, particularly in North America.

Schools like the State University of New York (SUNY) College of Optometry became known for advanced pediatric training, offering residents concentrated exposure to infants, children, and complex binocular vision cases (Duckman, 1994). These programs helped formalize knowledge that had previously been learned through mentorship or experience alone.

For the first time, an optometrist could intentionally train after graduation to focus on pediatric care.

Professional organizations solidify the specialty

As training expanded, professional organizations followed.

Within the American Academy of Optometry (AAO), pediatric and binocular vision began to gain formal recognition through dedicated sections and credentials. The Academy eventually established a Diplomate program in Pediatric Optometry and Binocular Vision, recognizing optometrists who demonstrated advanced expertise through examination, publication, and clinical experience (American Academy of Optometry, n.d.).

This mattered because it created a standard. Pediatric optometry was no longer defined only by interest but rather, it was defined by training, scholarship, and peer recognition.

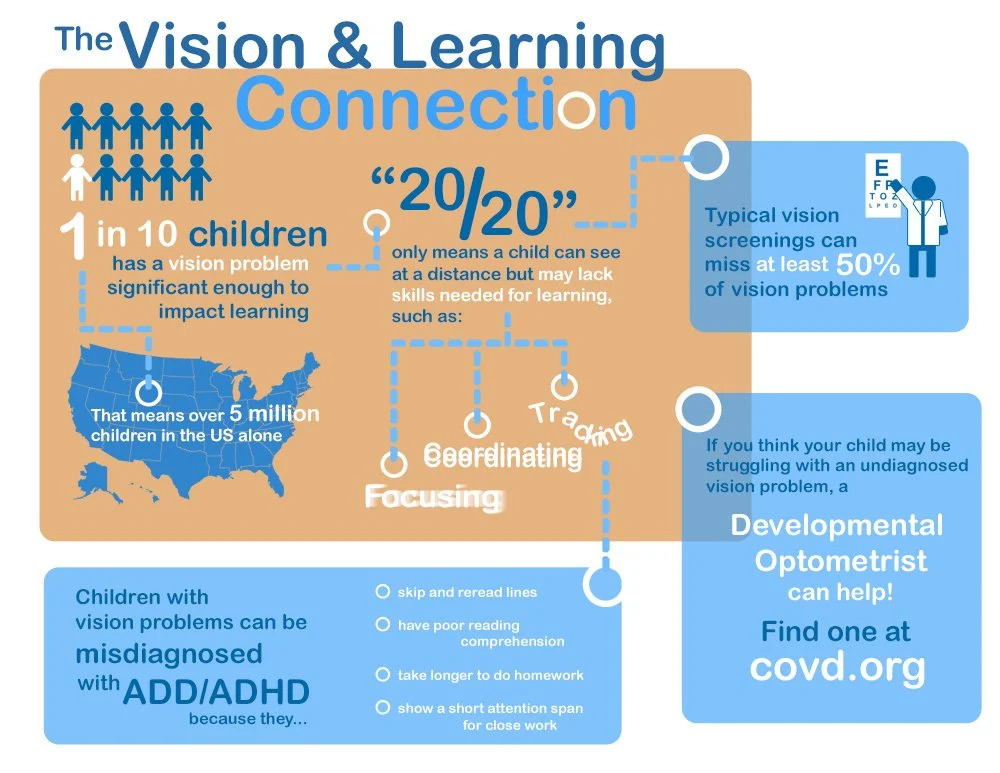

At the same time, organizations such as the College of Optometrists in Vision Development (COVD) continued to grow. Founded earlier, COVD expanded its fellowship certification (FCOVD) during this period, emphasizing developmental vision care, vision therapy, and pediatric patients (Sutton, 2005).

Not every optometrist agreed with every approach, but the presence of structured organizations reflected something important; children’s vision care had become complex enough to require specialization.

Textbooks and literature catch up

Another marker of specialization is literature. By the late 20th century, pediatric optometry had its own textbooks, rather than just chapters in general optometry manuals.

One influential example is Robert Duckman’s pediatric optometry texts, which consolidated clinical approaches to examining children, managing binocular vision disorders, and addressing developmental concerns (Duckman, 1994). Journals within optometry also published increasing amounts of pediatric-focused research, covering topics like amblyopia treatment, early refractive error detection, and visual factors in learning (Solan, 1988).

This helped shape how optometry students were taught and how new graduates approached pediatric patients.

Insurance, access, and public perception

The 1980s and 1990s also saw changes outside the clinic that affected pediatric optometry. Vision insurance plans increasingly included routine eye exams for children, which made pediatric care more accessible and normalized regular eye exams at younger ages.

As a result, optometrists became the primary eye care providers for many children—not just for glasses, but for ongoing care. This shift also changed public perception. By the 1990s, it was common for optometric practices to advertise care for “infants through seniors,” reflecting how pediatric care had become integrated into everyday practice.

Collaboration becomes more common

During this period, collaboration between optometrists and ophthalmologists also became more structured. Pediatric ophthalmologists focused on surgical and medical management, while optometrists increasingly handled refractive care, binocular vision management, and long-term follow-up.

Where pediatric optometry stood by the late 1990s

By the end of the 20th century, pediatric optometry had crossed an important threshold:

formal residency training existed

professional certifications recognized expertise

textbooks and research supported clinical practice

pediatric patients were routine, not exceptional

collaboration with other pediatric eye care professionals was established

Part 4 will move into the 2000s and beyond—public health initiatives, mandatory eye exams, InfantSEE, policy changes, and how pediatric optometry fits into modern healthcare systems today. We’re almost there!